Were early humans cannibals? New research says our ancestors likely practiced the ultimate taboo

Download MP3Cannibalism is one of our oldest taboos, and it might even be older than previously believed.

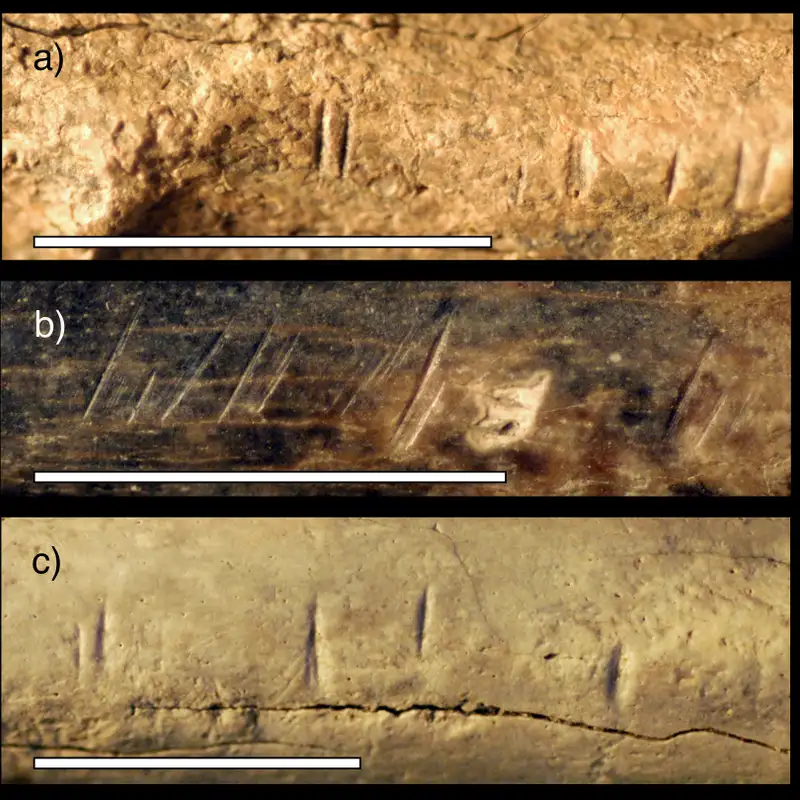

A new study coauthored by researchers from the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and Colorado State University have identified the oldest decisive evidence of humans' close evolutionary relatives butchering and likely eating one another. The study identified nine cut marks on a 1.45-million-year-old shinbone from a relative of Homo sapiens found in northern Kenya. The marks were compared to almost 900 individual tooth, butchery and trample marks created through controlled experiments. The analysis revealed that the cut marks were dead ringers for the damage inflicted by stone tools used in the butchering process at that time.

The 3D quantitative method behind this discovery was created by CSU Associate Professor Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist who studies the feeding behavior of early members of the human genus. The process employs high-resolution 3D scanners, typically used in the semiconductor industry, to create measurable models of marks produced through experiments on modern bones in order to compare them with those found on fossils.

Audit host Stacy Nick spoke with Pante about this important discovery, what it means for future fossil research and what was it that led our early ancestors to eat each other.

I want to talk a little bit about how this research got started, because CSU's role, this all began when you received fossil molds of cut marks and you got no other information at that time. Did it just it just arrive with a note saying, analyze this?

Well, Briana, Briana Pobiner from the Smithsonian Institution just said, I have some marks I'd like you to analyze. I mean, people send me molds all the time so we're always trying to analyze them as they come in. This was nice because it was just one mold. Sometimes I get 100 or so. So, this was a quick application. And my former M.A. student, Trevor Keevil, who's now a Ph.D. student, he did the analysis, the original analysis of it. And then as time went on, we just worked on writing up the publication and trying to be secure about what we were we were going to say because it is controversial in that one, this quantitative method that we are now using had never been used before so that people can have questions about how reliable that is. And then the other thing is any very early evidence of anything is always controversial and especially something as interesting as cannibalism, where what are the implications of that? Because as you go through time and you think about humans, normally cannibalism occurs in some type of ritual process. And for ancestors at this age, we have no evidence of any symbolic behavior or burials or anything like that where they would be doing something for a ritual process. So there's a lot of implications in terms of why are these marks there? Are they even actual cut marks and what do they mean in terms of what our ancestors were doing to survive in the middle of Africa, when resources are not always available? Most people, when you look for a cut mark, you look for contextual information. So where is it located? What is the angle of the mark relative to the other bone? What other marks are on the bone that could be related to this one? Because this method doesn't require any of that information and it's solely based on the actual morphology or shape of the mark. It doesn't require me to know anything, and so it removes the potential for bias.

What led you to believe that these stone tool cut marks suggest butchering for consumption rather than say, a weapon in a fight?

Weapon impacts are normally very different than this. These were slicing marks. There's also no evidence of weaponry at this time. So, we basically have pretty simple stone tools, no evidence of hafting them onto sticks or anything like that. There may have been wood implements that we don't know about, but that's always hard to say. In this case, we interpreted the marks through the lens of having looked at tens of thousands of animal fossils that are butchered for their flesh. And these had the same appearance, especially in that region, in terms of the size, the location and the orientation of the marks. So, for us, it was very clearly a case of some type of defleshing. And the other thing is, at that point, when you look at the musculature of humans, there's a number of muscles that attach there. You know, if you think about your calf muscle, that is basically where these marks are. So that's a pretty big packet of meat, should you be hungry. And it's also difficult to cut all the way through that. I was asked at one point, could the hominin have done it to himself for some other reason? And I said, well, that's a lot of flesh to cut through. That would be extremely painful. So, I don't think that's the case.

I apologize for my morbid laugh, but that is just such a visual.

Yeah.

Just the idea of that. But it makes I guess, a really giant turkey leg.

Yeah.

What does this finding mean for paleoanthropology? Does it change how we view interactions a million years ago?

I don't think it changes much because it's one example, and we don't really know what it means. We know there's another potential example that's maybe even older than this example, but that still needs further study. So, I would say it's interesting in that we didn't have evidence of this before, and it potentially suggests our ancestors were doing whatever it takes to survive. But we can't really say too much from a single bone. So, it's one piece of a puzzle that will continue to build on with future discoveries and analysis.

What's the next piece of this puzzle?

It's continuing to look through museum collections. This was found in a museum, and it was originally discovered over 50 years ago. So, the people who study the actual fossils of human ancestors typically don't have the expertise that myself and Brianna Pobiner from the Smithsonian Institution have. So potentially a lot of these marks are overlooked on fossils. They're often misinterpreted. So there's a lot of potential to build in that way. But also excavating more material is always enlightening. Human fossils in general, our ancestors --- I'm saying human, but our ancestors not quite human --- they're extremely rare in the fossil record, so we have to look really hard to find any of them. You could go your whole career without finding a single human fossil.

So, this all started with the reexamination of a fossil from a museum. What does that tell us about the potential value of using newer techniques to take a second look at things that we've already discovered?

It's only maybe in the last decade that people have started to use this technology to look at surface marks on fossils to get a better understanding of them. So, there's a bunch of different people trying different methods at this point. But in the past, it was just, "I'm an expert. I'm going to look at this and tell you what it is, and you need to believe me." So that's why we're finding a lot of errors in past interpretations that look at basic - we call them surface modifications or scratches on bones. So, you know, if you were relying on an expert, we don't really know how much of an expert you are. So, the advantage of using these new methods is we can now give a number of confidence. How confident are we in the interpretation? And that's something we've never had before. It's just based only on reputation alone. So that, I think, adds a lot of value. And I think we'll change a lot of things over time. It's just about getting access to the material to be able to do it.

The high-resolution 3D model was the first application to a fossil specimen of the 3D quantitative method that you developed. Can you tell me a little about that process?

I published a basic method of how you would measure a mark in terms of just the morphology -- the shape of it, how deep it is, how rough the surface is, basically what an expert looks for when they're looking at a mark. So, I tried to teach a computer to do what I do. I've scanned other fossils, but I haven't published that yet because we needed a large sample of marks from different processes. Those include animals stepping on bones, which strangely looks a lot like cut marks on bones and crocodiles biting bones also can look like cut marks. We needed to look at a lot of carnivore tooth marks as well, and also the impact marks from humans breaking bones. So that took a long time to collect. In the past we used an older scanner, and it would take two to three hours to make one 3D model. Now we can make one in maybe two to three minutes with an updated scanner that we were able to secure.

So, there's one other fossil, a skull first found in South Africa in 1976 has previously sparked some debate about the earliest known case of human relatives butchering each other and its age estimates range from 1.5 to 2.6 million years old. Dr. Pobiner is looking to reexamine that skull to see if the cut marks are similar, and I wondered if you're going to be possibly working with her on that research as well?

Yeah, we just submitted applications to do it, so and don't anticipate any issues, so we'll probably do that this fall.

So more exciting research to come.

Hopefully. I mean, who knows what it will say. This other specimen is a skull, and the location of the marks is not really consistent with what I've seen when humans deflesh other human's heads. So, we'll have to take a look at it. And it's in a context that is in a cave, so rockfall happens and a lot of things so you can a lot of different types of processes can make a mark on a skull that aren't actually butchering marks. Nonetheless, the people who studied it were some top scholars, but it was over 20 years ago. So, our methods have improved. And we hold ourselves to different standards than we did back then. So, it'll be interesting to see what the results show.

There's something about when you use the phrase 'defleshing the head,' that's just, I have a reaction to it. Did you ever think this is what you'd be studying?

No. I mean, getting into this literature is, I've been doing it through another site as well. So, the cannibalism literature is very difficult to sift through because there's been a lot said. And the issue with cannibalism is we like to simulate what happened in the past and know exactly how it happened by doing experiments. But we can't just go and cut up a bunch of humans for different purposes, ritual and, or consumption. So that's been a challenge in terms of that literature, because most of what we say is based on sites where we really don't know what happened. And then those sites are used to characterize a pattern that we should expect at other archeological sites. And that is something that is really prone to error. And that's why we see so much disagreement in the literature about any site that has evidence of butchery on a human. There's any number of reasons why. And then the other complication is what humans do to each other after death is incredibly diverse and surprising. Humans will bury each other, then dig each other up, then remove all the flesh, and then rebury it. They will smash the bones open. They will burn the bones. There's many different ways that people practice mortuary practices, and that makes it incredibly challenging to even know whether a ritual occurred, or this is consumption. So that is kind of one of the things that is most frustrating about trying to infer anything about a human butchery mark. Because even these marks on this tibia, when other researchers were questioned about it, many of them questioned whether it could be a ritual. And for me, the lack of symbolism until a million years after suggests that's not the most likely scenario. But you can never really rule it out given it's only one bone.

There's such a fascination with this topic.

Probably just so many good movies about cannibals. And now everyone's into Yellowjackets, Silence of the Lambs. It goes on and on. And it's also just like disgusting to think about for most people. You can't imagine eating another human. And that's also probably why it's mostly not just eating another human to eat another human. There's got to be some other reason to do it than just nutrition. It could be starvation; it could be warfare and disrespect of your enemies. It could be ritual or some burial process, the list can go on and on. And that fascinates people, like what we don't know and what we could know. And it's just unimaginable to most people to take a bite of another human. And there's always these examples throughout human history where we see these individuals that have done this, and they become really fascinating to the public. So, this is just, I think, an extension of that. I mean, I can imagine that people will start saying that cannibalism is so deeply rooted in us, it's not unnatural or things like that, but we really don't know. Human behavior is so diverse. And this one example is just an interesting piece of information that we can take and hopefully build on with other discoveries.

It's kind of the ultimate taboo.

Yeah, it's definitely the ultimate taboo. I would say, even more than murder, obviously. And there's just been so many examples of it in recent times even, that are just shocking. You know, Jeffrey Dahmer, of course, and others. So, I think that's why people get this fascination.

Yeah. That idea of if we were starving, how far would you go?

Yeah, I mean, I, I think most people will go pretty far to survive. But you never know until you're in that situation. Survival cannibalism is probably the rarest type of cannibalism, to be honest, and it's something we see in more recent times but don't really have that much evidence for in the past. So, it's interesting to think, was this individual practicing that and at what point did humans start doing that?

If that's the rarest, what's the most common?

Ritual cannibalism in more recent times is the most common. With modern humans, whether it's true or not, it's hard to say because people don't really know what happened. But that's most often what people say, it's a ritual behavior. Even with Neanderthals, we are typically inferring ritual behavior. The earliest example of established cannibalism is around 800,000 years ago, but that has been inferred to be due to warfare and for consumption. So, it wasn't some type of ritual process, according to the authors who studied it.

Does this finding change how we view our early ancestors?

It's certainly surprising because it's so rare in the fossil record, but we really don't know how rare it is because human fossils are so rare. What we see with early humans is they are eating pretty much anything they can get their hands on. They're scavenging food, they're consuming everything from small antelope all the way up to elephants. There's even a site I've worked on where they consumed a hyena. Which if you've ever seen a hyena, they're quite disgusting and it's not really appetizing. Most people now do not eat carnivores, but I know there's certainly cultural exceptions. So, they are doing everything they can to survive. I think the thing that made us so successful is that we are able to respond to so many different environmental conditions and survive through them. So, during this time when humans evolved in Africa, the landscapes are becoming very arid and dry. They are starting to compete with carnivores for food because they're eating meat and marrow, and they're also trying to rely on plant resources that may becoming less reliable in terms of their location. And the species that may have inflicted these marks --- homo erectus --- was also the first to disperse out of Africa. So, you can imagine as you're moving through longer distances, you're less familiar with those environments. Think about going to a neighboring town, where is the grocery store even. Now, try and figure out where a source of stone tools is, where reliable plant food are, and where you can find sources of water where you can also possibly interact with animals and consume them. That, to me, is what characterizes early human evolution, being extremely flexible and capable of adapting to so many different environments.

So, maybe don't be so hard on our early ancestors for their choices that they made.

No, it makes us who we are in that we are incredibly adaptable. I mean, just look at where humans live now across every environment with the exception of the ocean. So, it's pretty incredible that we are able to do that. And that reflects all the behaviors we've adapted throughout our evolution. Clothing, for one, is a big one. Fire. So, all those things are really important to becoming human.

Well, thank you so much for being here.

Thank you.

That was CSU paleoanthropologist Michael Pante speaking about the recent discovery of the oldest decisive evidence of potential cannibalism. I'm your host, Stacy Nick, and this is the Audit CSU's new podcast, featuring conversations with CSU faculty about everything from research to current events.