The mother of invention: Sue James talks about changing the world one patent at a time

Download MP3Transcript

INTRO: Sue James is the vice provost for faculty affairs at Colorado State University and is responsible for working with faculty, deans, vice provosts, and vice presidents to ensure a well -supported faculty along with exemplary teaching and learning practices. But James is also a professor of mechanical engineering, the founding director of CSU's School of Biomedical Engineering, and a prolific scholar and inventor in the field of biomaterials. She's also one of three current and the only female National Academy of Inventors fellows from CSU. Committed to giving back to her community, James has been involved with many service organizations over the years, both internal and external to CSU, including the CSU President's Commission on Women and Gender Equity and the Society of Women Engineers. Today, I'm talking with James about her career path, working to pave the way for other women engineers and her many inventions along the way.

HOST: I'd like to start at the beginning and just find out a little bit more about what initially got you interested in engineering and specifically biomedical engineering.

JAMES: I was always pretty talented in math and science as a little girl, and I was fortunate to have parents and public-school teachers who encouraged that. When I got to high school, I had two advanced placement classes in the sciences, physics and chemistry, and some wonderful high school teachers there who really helped steer me towards engineering, along with my parents. And then I think the biomedical part came in when I started looking at things that I could major in as an undergraduate, and I wanted to make a difference in the world. And for me, health care and improving medical care for patients was something that really rang true for me.

HOST: Was it difficult at that time as a woman engineer?

JAMES: I think the first time it really kind of smacked me in the face was when I was an undergraduate studying metallurgy, and I won a scholarship from the Iron and Steel Society. I went to my first conference ever, the Iron and Steel Society Conference, which had, I don't even know how many people were there, thousands and thousands of people. I walked up to the registration desk, and they turned to me and they said, “Oh, you must be here to register for the wives' program.” And I just looked at them like, “Well, no, actually I'm here because I'm your scholarship winner.” But that was a conference where literally I was probably the only woman at the conference.

HOST: Oh, wow.

JAMES: And that was, I think, maybe my first super wake-up call to the fact that I had gone into a very male-dominated field because I'd seen it in class, but that was not class. That was the industry itself.

HOST: What was your reaction to that?

JAMES: It won't surprise you that I have a pretty strong personality and independent streak and did even back then. I probably took it as more of a challenge than something to run from, but it did feel weird and it felt unsafe and insecure just as a young woman surrounded by thousands of men at, you know, the happy hour for the conference and things like that. But it also, I think, raised in me the challenge and helped me focus even more on the idea that if there's one thing I could do in my career, it's try to improve the representation of women in my field.

HOST: And I believe, I was looking at your CV, and you minored in women's studies as well.

JAMES: People are always a little surprised when they look at my educational background and see a bunch of engineering and women's studies. I think it did play into that. It's something I've always been passionate about and certainly realized that I had a minoritized identity as a woman in engineering very early on. The reality is that's still true today. I think that's part of why I chose women's studies as a minor when I was an undergraduate and I learned a lot and it was also very different from the engineering I was studying. It really helped to round out my studies and my thinking.

HOST: Over the years, have you seen a lot of changes as far as how far women have come in engineering or maybe not? You're hesitating, so I'm guessing not as much as we'd like.

JAMES: Yeah, so I've seen changes for sure. And do we have more women represented among engineering students and in the engineering profession today than when I started my school and my studies 30, 40 years ago? Yes. But have we come far enough? Not even close. And so, I do find myself getting frustrated sometimes when I look at women in engineering now compared to when I started as a student so many decades ago and sometimes feel like I'm surprised we haven't made more progress. But yes, we have made progress and it's been delightful to watch that and to be part of it.

HOST: What led you to focus on academia rather than pursuing a career on the industry side?

JAMES: Well, I actually did go into industry after graduate school. I thought about going into industry right after my undergraduate studies, but when I was a metallurgical major as an undergraduate student, which means studying metals and alloys and things like that. And when I was looking at the jobs that I could get with my bachelor's degree, I just decided it wasn't going to be challenging enough for me. And so that made me decide to go to graduate school. And then when I finished graduate school and I finished my Ph.D., I did actually go to work in industry because even though I knew I thought I wanted to go in academia, I thought it would make me a better engineering professor to have that industrial experience. And it did. But I also only spent about a year in industry because I really came to understand that I really enjoyed research, and I found it very rewarding and especially academic research, where you get to go deep and broad into the things that you're studying.

HOST: As I mentioned in my introduction, you are a prolific inventor. You have more than 30 patents to your name. I wonder if you could tell me a little bit about your first invention.

JAMES: Yeah, my first invention that I got a patent on was when I was in graduate school at MIT. And I worked for both an advisor at MIT, who was a material scientist, as well as an orthopedic surgeon at Mass General Hospital, who was a hip replacement surgeon. And he was a very prolific inventor himself, which is probably partly where I kind of got that mindset. My very first invention was around total hip replacements and what's called bone cement, which is an acrylic material that's used to hold hip replacements to the bone itself. And it was an invention designed to prevent air from being sucked in at the interface as the prosthesis was inserted. It was something that the surgeon would use during surgery to try to improve the placement of the hip replacement.

HOST: I think it's always fascinating to talk with the people who have created something about the process. And I'm wondering, did you know when you were at the start of this that you were creating something new and that that's where it was heading? Or was there an aha moment?

JAMES: I don't think I knew at the beginning. At the beginning I was doing research like a good graduate student and trying to solve a problem like a good engineer. I was very focused on a problem we had identified with the placement of the hip prosthesis and then worked on developing what then became patentable technology. And because I worked in a laboratory where they had patented their technology before, my advisor there was the one who said we should probably file a patent on that. I don't think I knew ahead of time, but that really helped me think about going forward in my career, think about inventions. I did start thinking about it ahead of time more in my career as I moved forward.

HOST: To have a patent at such an early stage in your career, that had to be really exciting.

JAMES: It was super exciting. I remember my parents were really excited. And of course, most patents don't come to much, right? I mean, I'm an inventor. I have a lot of patents. Only a few of them are related to the technologies that I have either transferred to use in humans and in the clinic or are trying to transfer. And that's just the reality of patents. I mean, you don't know which things are going to end up being something that get developed and which aren't.

HOST: Do you ever have when you're working on a problem, do you have that moment where you kind of wake up in the middle of the night and you're like, I've got it. I've got the solution.

JAMES: Yeah, it's funny you should say that because I actually had an aha moment in the middle of the night. It was when I was working in industry, I mentioned that earlier, and I had decided I was going to go back to academia and try to get a job as an assistant professor somewhere, which is how I ended up here at Colorado State University. And I was thinking about a research program I would start and how to build off of my graduate work, which was in hip replacements, but also be different from the laboratory I had come from. And I was thinking about the materials that are used in hip replacements, which are synthetic, human-made materials that actually are not very compatible with the body and trying to think about how to make those materials more compatible. And so, I'd been thinking about it a lot for the month or two proceeding. And I actually kind of woke up in the middle of the night with an aha moment about how to take the strength and durability of a human-made synthetic material, but still make it look more like a biological material, so that you would have better compatibility but still keep the strength of that engineered material. And it really was, I woke up in the middle of the night, grabbed a piece of paper, wrote down some ideas, went back to sleep. But that did form a kernel for a lot of the work I did as an academic, work that changed and evolved over the years as you do research, as anybody who's done long-term research. It never turns out the way you think it's going to turn out. But those initial ideas are still very important for sort of getting things going.

HOST: And that led to — that item is in clinic, correct? That's an actual — It's currently available. That's got to be really exciting, too, that you know that something that you created is out there helping people right now.

JAMES: It's exciting. It's also a little scary. Those implants are called biopoly. They're orthopedic implants that are used in the knee and other joints in many thousands of patients and doing well. It's very exciting. And that's why I went into the work that I do. I think about that all the time. It's also scary because it's in people's bodies. And I also know from the work that I do that implants fail inside people's bodies. And that causes problems. So far, we haven't had any bad failures but that is — that's the flip side of being excited is also the risk and being a little bit scared about the fact that you invented something that's now in the knees of people who are walking around.

HOST: Well, you wanted a challenge.

JAMES: There you go.

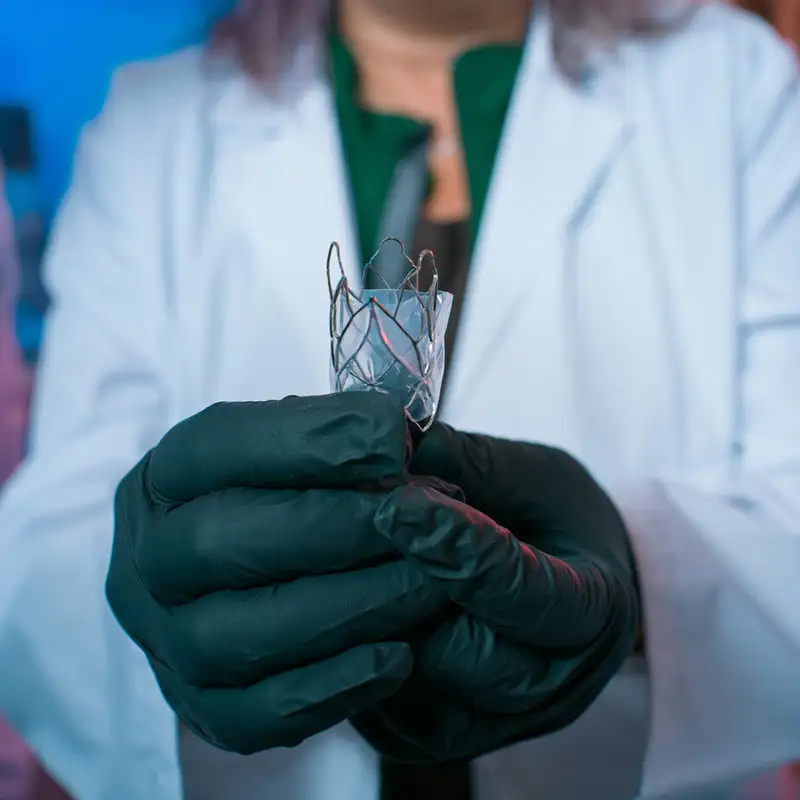

HOST: Now, more recently, you've created a device to replace diseased heart valves. Your startup company, YoungHeartValve, is currently working to commercialize that. Tell me a little bit about how that works.

JAMES: Yeah, so YoungHeartValve is a startup company that I have. My co -founder used to be a professor here at Colorado State University, although he's currently at Georgia Tech. The biomaterials part of that invention was, how do we make a heart valve material that is not made out of animal tissue because most commercial heart valves today are made out of animal tissue. And that, of course, means the people who make heart valves are also farmers and ranchers and have all kinds of supply-chain issues related to the fact that what they build is coming out of animals. That's just one example of the problems with animal tissues. So, how do we replace the animal tissues? And then how do we solve that compatibility problem? Any time you put a synthetic material into the body, the body doesn't want it there. And we've all had that experience. If you've ever gotten a splinter in your finger and you weren't able to pull it out, your body will push it out eventually, right? That's called a foreign body response. And that's just one example of what your body does when you put a synthetic material inside of it. Well, then if you take a synthetic material and you put it into the bloodstream, like a heart valve. All the blood in your body flows through your heart valves all the time. The only thing that's really compatible with blood is the inside of your cardiovascular system. The lining of your vessels, your heart valve leaflets, and your natural heart valve are very compatible with blood. Our challenge was to create a material that was strong and durable, but that was more compatible with blood than your typical human-made materials. And that's really the nexus of the inventions that are behind our YoungHeartValve work. We're using synthetic polyethylene materials, but we've put a biological molecule that naturally occurs in your body into the material. From the blood's point of view, it looks more like your natural body, but it's actually this very strong durable plastic that will last a lifetime.

HOST: I'm imagining a Slip ’N Slide.

JAMES: You are not the first person to make the Slip ’N Slide analogy, actually. In fact, it's a very good analogy for what we do because the biological material that we put into the plastic is essentially snot, for lack of a better way to describe it. I should have warned you I was going to say that. But when you think about snot, and then to get really gross, wet snot, so not dry boogers, but like when you've got a really bad cold and you've got really wet, flowing sinuses, that is mostly made out of what's called hyaluronan, which is the material that we put into our heart valves. So, you end up with a strong, durable plastic with a Slip ’N Slide, slippery, snotty surface.

HOST: I have so many images running around in my head right now. This is going to be weird, but how do you get the hyaluronan? Is it created, the hyaluronan?

JAMES: How do you get the hyaluronan itself? That's a perfect question. You can get hyaluronan, you can get it from natural sources. For example, rooster combs on the top of a rooster's head have a lot of hyaluronan in them. In factories where they process chickens, you can also get hyaluronan out of rooster combs. It occurs naturally in places like seaweed. But probably about 30 years ago or so, a lot of smart engineers and scientists also figured out how to create hyaluronan in fermentation techniques and in bioreactors. The hyaluronan we used is commercially produced that way.

HOST: Okay, commercially produced snot.

JAMES: Yep, exactly.

HOST: We talked about this a little bit earlier, but again, that's something that even more critically, that people are going to be relying on, that your inventions are literally saving people's lives. When you started your career, did you think that that's where you'd be headed?

JAMES: I didn't because I started my work in orthopedics and if your hip or your knee replacement fails, you don't die catastrophically. So hip replacements and knee replacements do fail, but usually we can go in and fix them. If your heart valve fails catastrophically, it can kill you, right? It is a much higher-level risk implant in a lot of ways. I don't know that I was thinking that when I started my career, but I certainly was thinking about that as I deliberately pivoted from the orthopedic world into the cardiovascular world and making heart valves.

HOST: What inspired that pivot?

JAMES: I would put interdisciplinary collaboration down as the reason that that pivot happened. I was the head of the mechanical engineering department here at the time and Prasad Dasi, who's my co -founder of YoungHeartValve, was a relatively new assistant professor in the department at the time, and he's a heart valve expert. He knew what needed to be solved in the heart valve world, but wasn't a materials expert and he and I were talking about how we might collaborate on some research together and that's where these ideas came from.

HOST: Now it's not commercially available yet, so it's not in clinic?

JAMES: Correct. Where we are right now is our company YoungHeartValve has funding from the federal government in the form of what's called an SBIR, or Small Business Infrastructure for Research Grant. And what we're trying to do right now is reach what we call design freeze on our heart valves, get to the point where we have a fairly final design and go into long -term chronic animal studies, which we do in sheep, so that we can show the durability and the efficacy in the animals before we go to our first in-human work.

HOST: Your creations take a long time to get from the aha moment to the actual in-someone's-body moment. What's the timeline for that?

JAMES: If there's one characteristic that I have as an inventor that has served me well, it's patience. The aha moment I mentioned when I was thinking about going back into academia, it took 10, 15 years before those ideas finally made it to the clinic in the form of orthopedic implants and knee implants. The heart valve work we're talking about now started probably about 15 years ago. It takes a long time. And as somebody who's mentored many graduate students in my career, one of the things I've told a lot of graduate students over time is you may not believe it, but the work you're doing now could end up in an implant 15 or 20 years from now. And that actually happened to some of my earliest graduate students because the work they did, and they were co-inventors on the patents, is what led to the current implant technology.

HOST: You've helped usher quite a few students into this career path and into STEM careers. And I'm wondering why that was an important area for you to focus on.

JAMES: You know, that's why I work at a university, right? I love education and I love mentoring students. I say young students now because I'm so old, but when I was a young faculty member, some of them were the same age as I was or even older than I was. But I could be a researcher, just in industry or in a laboratory where there was no academic component to it. But I came to a university because I love education and not just mentoring and advising students, but also teaching students in the classroom, which has been a big part of my career as well. It is just so fulfilling to do that kind of work and you feel like you're really making a big difference, not only to those people's lives, but to your discipline because the students I've mentored are going to go on and do even more amazing things than I've done in my own career. It's a great way to help make contributions not only to individuals, but to the overall field.

HOST: Thank you so much for being here.

JAMES: It was my pleasure. Thank you, Stacy.

OUTRO: That was Sue James, CSU's vice provost for faculty affairs, professor of mechanical engineering and the founding director of the CSU School of Biomedical Engineering. I'm your host Stacy Nick, and you're listening to CSU's The Audit.