How history may help solve the maritime mystery of ‘milky seas’

Download MP3(This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity)

INTRO: Welcome to Colorado State University's podcast, The Audit, where host Stacy Nick talks with CSU faculty about topics ranging from their latest research to current events.

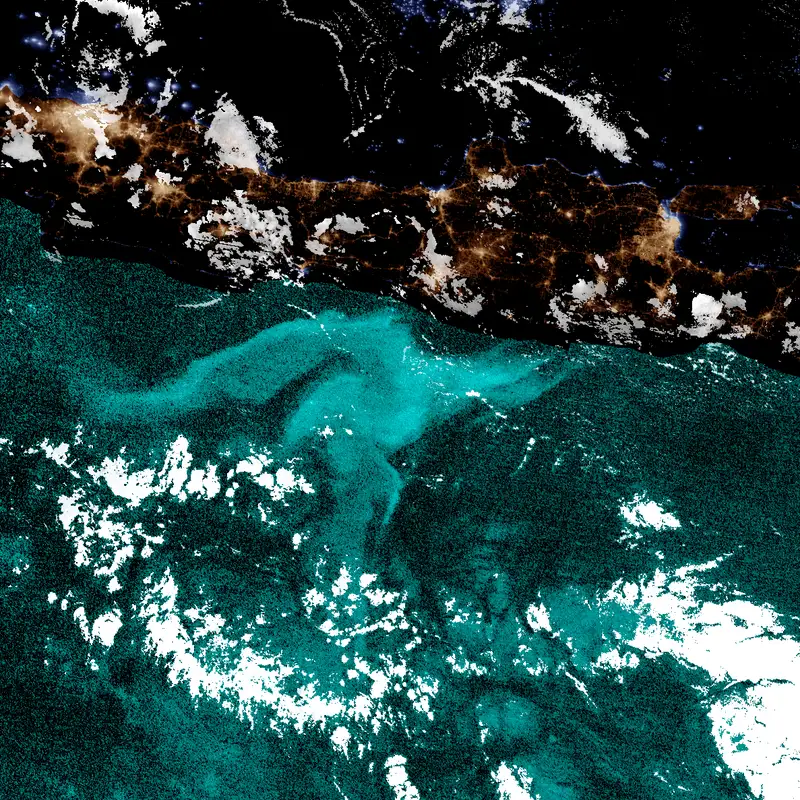

HOST: Imagine being a sailor in the 1700s and suddenly, in the pitch black of night, the sea begins to turn a fluorescent green, illuminating the ocean like a giant nightlight so brightly you could read by it. Now we call this peculiar occurrence milky seas, but more than 300 years later, researchers still don't know much more about them than those sailors did. Today I'm speaking with Justin Hudson, a doctoral student in atmospheric science at Colorado State University. Hudson has created a global database of milky sea events in an effort to learn more about this illuminating phenomenon.

HOST: What exactly is a milky sea? What does it look like?

HUDSON: The best way to describe it to sort of a modern viewer would be if you imagine those sort of like glow-in-the-dark stars that children put on their ceiling in their bedroom, just sort of imagine that kind of green, pale, even glow just every direction where you look on the ocean. So, sort of, imagine you're on a boat in the middle of the night, there's no lights on, the only light is sort of the stars above because it's like a new moon. Very dark. Then suddenly the ocean, which normally was very, very dark compared to the sky, just becomes this bright green-white color. And everywhere you look is just that even green — like those glow-in-the-dark stars you put on ceilings. That's sort of the best way to imagine it. But it's so strange that it's kind of hard to really picture yourself in that.

HOST: So that's what it looks like, but what is it? Is it a plant? Is it like algae? Is it an animal? Is it, I mean, when you say the phrase bioluminescence, I typically think of like fireflies.

HUDSON: So, bioluminescence, like as you are kind of getting into, comes in so many different shapes and forms across nature. There's mushrooms and insects and sort of like, you know, angler fish with their little lure. But milky seas, we believe, are caused by bacteria. Very, very large numbers of bacteria. I think it's in the trillions of bacteria per milliliter of water. sort of level of how many there need to be spread out over hundreds to thousands of miles.

HOST: You say we “believe.” So, it's not really known what this is.

HUDSON: Yeah, so we strongly suspect based on sort of the characteristics of the light and how long it lasts that it is bacteria. As a data point to further that idea, there was a lucky encounter by a research vessel in 1985 with a milky sea. They found this bioluminescent bacterium called Vibrio harveyi around there, which lines up pretty well with what the glow of this milky sea looks like. So, it's why we strongly suspect this, or due to all of like our understanding of what milky seas are, what these bacteria do lines up really well. But again, it's a question of how do you take some of the smallest organisms on Earth and have them engage in some behavior that's half the size of the state of Colorado.

HOST: So, it's tricky.

HUDSON: Yeah.

HOST: Some people maybe would say, well, why can't you just go out to the ocean and just study this? It's not quite that easy, right?

HUDSON: So, it's really hard to get to a milky sea. The locations where they tend to happen are pretty far, well, decently far from shore, so you need a very big boat to go out there safely. You also need to be able to know when one is going to happen, because if you go out there and you're wasting your time and your money and they don't happen every year in the same spot, there are places where milky seas happen often, but you might have like a seven, eight year gap in between milky seas occurring, and if you get unlucky in that you went out on the wrong year, well, that's it, you blew all of your research money. So, if you really want to study one, you have to be able to predict when and where they're going to happen.

HOST: Are they rare? Is there a milky sea season or a set of conditions that make for prime milky sea events?

HUDSON: Depends on where you're looking at. So, there's three main regions on earth where milky seas happen. The first one is where about 60% of all milky seas we know about have ever occurred. And that is in the Northwest Indian Ocean near the coast of Somalia or sort of the Southeastern edge of the Arabian Peninsula. In that region, the majority of them happen around August, July and September. Then about a third of them occur in January/February. The other two regions where they occur, one is just south of the island of Java in Indonesia, so northwest of Australia. Whenever they happen near Java, it's pretty close to August. You might have them maybe in July or maybe in September, but August is the peak time there. Then the third region is called the Banda Sea, which is north of Australia, and there's all those islands there, which we call the Maritime Continent. and in that region, milky seas happen mostly in August.

HOST: Now, as we mentioned, your research has you going back through about 400 years of observations, eyewitness reports from ship logs and diaries, as well as modern scientific records from satellite imagery. How did you go about finding these reports?

HUDSON: The majority of them, I was fortunate enough that, so back in 1993, there was this man named Peter Herring, and he had a graduate student at the time named Maggie Watson. The two of them had, working together, combed through a database of records collected by the U.K. government of bioluminescence, and pulled out just the ones that they suspected were milky seas, based on their expert judgment. and they put together a database and published it in 1993. Now, in the 30 odd years since then, their database got lost at some point, which was kind of a bummer because that meant there really wasn't any data to study milky seas for about 30 odd of years. But Peter Herring fortunately had kept all of his records before he retired. He was very gracious and generous and donated his old records to me and my co-author and advisor, Steve Miller, to work on this project. So, I had sort of as a starting off point. I had all of his records, which altogether make up about half of the database. Then there is another person who had also tried to make their own milky sea database named Tim Wyatt, and he had also generously donated his records to us. Together that gets us about 70% of the way to the full database. The rest came through this journal published for about 80 years by the U.K. Meteorological Office, called the “Marine Observer.” The basic idea was that following World War I, people were really interested in how to better predict weather out on the open ocean. To that end, they put together this journal. The idea was that people could voluntarily take weather observations and send them back to the journal, as well as other things they saw, such as weird astrophysical phenomenon, weird weather patterns, or even things they saw related to biology. So, there's all these reports of like, “we saw dolphins here,” or “this bird flew onto our boat, it hung out with us for two months, and we made sure we went back to where we picked up the bird just to be safe.” But one of the main things they wrote in about was bioluminescence. Over the 80 years of this journal being published, people wrote about bioluminescence they saw out in the middle of the ocean. Now there are all sorts of rare and exotic forms of bioluminescence, but the one I really focused on was milky seas, obviously, and so I went through and read all 80 years of journals from the “Marine Observer.”

HOST: A little light reading.

HUDSON: (laughs) Yeah, very light reading.

HOST: Then how did you get accounts from even further back?

HUDSON: People have, since at least 1855, tried to put together databases of milky seas to catalog them. I was able to find their publications, use those as jumping off points to find their sources or their records. Fortunately, we also live in a time where people have had the great foresight to digitize old documents. So, there's all these books or newspaper articles stretching back to the 1700s or even earlier that had been digitized and set up so that you can actually just search the documents. Google has led sort of the way in doing a lot of that archiving work. By using the various databases they have I was able to find a lot older records in addition to using those older scientific publications. But the oldest one I found was actually entirely by chance. I was combing the library here at CSU. There's a shelf in the library at CSU which is just journals or diaries of ship captains or from ship voyages. So, it has the various first circumnavigations of the globe and things like that, like surviving diaries from then. And there is a set of islands in the Indian Ocean called the Keeling Islands. Well, that's one of their names. I think it has a different name now. I'm blanking on what it is. but they were a set of uninhabited islands named for the ship captain who found them. And there was a diary by Captain Keeling just sitting on the shelf and I was like, well, he was in the right area of the world. Let's just read through the diary really quick and see if he saw a milky sea. And he did, right off the coast of Somalia in the middle of August, right where you would expect someone to randomly encounter one. So, the actual oldest record I have was purely by chance.

HOST: The sailors of that time, what did they think it was? Did they think it was natural? Mystical? What's their experience?

HUDSON: Yeah, so Captain Keeling's diary didn't really go into what he thought it was. He describes it as I can actually pull up his exact quote: "We fell in the night into a white water like an extreme shoal but had no ground at 60 fathom line." And describing a milky sea like a very like shallow shoal of water is actually a very common description that you see later on which is why based on sort of the time of the year and the exact location that it sounds like he encountered a milky sea, but that was sort of extent of the observation. That's pretty standard for a lot of these records, a very matter-of-the-fact because they come from deck logs and there isn't that much space in some of these to really write a long description. But there was a scientific paper read before the Royal Society of London in 1772 by this man named Captain Newland. and he had encountered a milky sea in August of 1769 while sailing around in the Arabian Sea. And so when he eventually got back to England, he went to the Royal Society and talked about what he saw, but he also mentioned how he pulled up a bunch of water from the ocean, took it into a dark room in the boat, and examined it the best he could with his naked eye. And his conclusion was that milky seas were caused by some unknown microscopic organism. and that someone should figure out what exactly it was.

HOST: And all these years later, we're still trying to figure it out.

HUDSON: Yes.

HOST: Well, if you wouldn't mind, let's have you read a few of these observations. Some of these are really almost poetic.

HUDSON: Yeah, I can. Let me pull up some of the more poetic ones for you. So, this one is taken by Captain Kingman of the Shooting Star in 1854, and I believe he was near Java. "The whole appearance of the ocean was like a plane covered with snow. There was scarce a cloud in the heavens, yet the sky appeared as black as if a storm was raging. The scene was one of awful grandeur. the sea having turned to phosphorus and the heavens being hung in blackness and the stars going out seemed to indicate that all nature was preparing for that last grand conflagration which we are taught to believe is to annihilate this material world."

HOST: Oh wow.

HUDSON: From his perspective, he thought this was the biblical apocalypse. Cause if you've ever had the opportunity to be out on a boat in the middle of the ocean at night, it's very dark, but the ocean is very much noticeably darker than the sky, especially at the horizon. So, from his perspective all the world was just flipped upside down; suddenly the ocean is what's glowing and the sky is dark.

HOST: It's so beautiful the way he writes it, but I feel like that would also be extremely terrifying.

HUDSON: Yeah, and a lot of the accounts that I get are just very matter-of-the-fact: we encountered white glowing water here. So, we don't really get that. But when someone does provide a more emotional account, you definitely get the sense that they thought everything had just been turned upside down, like the whole world was just awry.

HOST: Can I have you read maybe one or two more?

HUDSON: Yeah, this one is from a confederate, I guess “privateer” is the correct word. During the Civil War, his job was to sail around the Indian Ocean disrupting shipping and trade. This is by Captain Raphael Sims of the CSS Alabama from 1864: "At about 8 p.m., there being no moon but the sky being clear and the stars shining brightly, we suddenly passed from the deep blue water in which we had been sailing into a patch of water so white that it startled me, so much did it appear like a shoal. The patch was extensive. We were several hours running through it. Around the horizon, there was a subdued glare or flush as though there were a distant illumination going on. Whilst overhead, there was a lurid dark sky in which the stars paled. The whole face of nature seemed changed and with but little stretch of the imagination, the Alabama might have been conceived to be a phantom ship, lighted up by the sickly and unearthly glare of a phantom sea and gliding under the pale stars one knew not whither.”

HOST: A maritime mystery.

HUDSON: Let me find a good, more modern one. This one comes from two members of the U.S. Navy from 1980, Lieutenant Chris Tolton and Reid Hinson. "At about 1930 to 2030 hours, Reid Henson announced something unusual out on the seas. Much of the crew went out on deck, and we were amazed at what we saw. It was night already and dark. It was like we were in the Twilight Zone and peering at a negative of the real world. The seas were glowing a phosphorescence as far as you could see all around us. The ship was darker than the seas. The sky was darker than the seas. Normally the seas are the darkest of all. The phosphorescent was uniform and a bit lighter green or whiter than the normal screw-generated green phosphorescent, kind of like the glow in the dark plastic stars you buy your kids. There were no breaks in the phosphorescence even with the waves. In this example, I didn't see any holes of dark water, but the wave foam was dark against the glowing water. I don't know how deep it went, but it appeared to be deeper than just the surface water, more than several yards deep."

HOST: These are amazing, but besides just being beautiful and connecting us to history, this database that you're putting together has a pretty important goal.

HUDSON: There were a few different goals with this. The first one was, as I as alluded to earlier, just actually creating a data set to study milky seas with. There had been several previous attempts throughout history to catalog and record milky seas, at least in sort of the English language, that I know of. Probably many others in languages I just can't speak that well. All those records in the English language have just been lost due to various reasons over the years. There was one in 1855. There were a couple in 1931. There was on in 1965. Then there was the one I mentioned in 1993.

HOST: The missing database.

HUDSON: We have the papers to go with it, the maps they made, but that's about it. Beyond that, other than the records that they put specifically in the papers and sort of maybe doing your best to estimate the exact location off of these old grainy maps, there wasn't much data to really dig into. There was some work done by my advisor and a bunch of his coauthors in 2021 where they used a satellite sensor called the VIIR's Day/Night Band to find milky seas and satellite imagery and catalog them between 2012 and 2021. They found 21 milky sea observations that way, which was a pretty good and substantial amount and shows that the sensor is good at finding milky seas. But that was kind of the extent of the data record, that small number of satellite events in which few events where he had interviewed people, like that last one I read by the two people from the U.S. Navy. That was an interview done by Steve. But other than that, there wasn't that much data. So, we thought let's get together a data set to begin to really dive into milky seas and understand when and where they happen and then we can use our knowledge of that to back out what actually maybe is making them happen. What phenomena or behavior of the atmosphere and the ocean is driving these extreme events? That way we can actually start to figure out how predictable they are and how feasible it would be to get someone out there at the correct time to sample it properly.

HOST: Besides just looking really cool, I'm wondering, what do we know about milky seas as far as the impact that they might have? Is there a negative impact? Do we have any idea?

HUDSON: We don't know enough to have a true solid idea, unfortunately. It's one of those things where we need to know more to even know how important they are. A couple things that I think do drive why we should look into them is that the bacteria that we suspect causes milky seas, Vibrio harveyi, is a known pest species and it can negatively infect fish and crustaceans. For people who farm those organisms, having a Vibrio infestation can wipe out their — “crop” I guess is the right word. In the regions where milky seas happen, fishing is one of the main economic activities. So, if milky seas occurring negatively impacts the fishing that year, then that means this is a major economic thing they should probably keep track of and understand to better forecast what's going to happen or even know we should maybe fish somewhere else. Another reason is that the Earth's carbon cycle has all of these different things that play into it. But one level of that involves how bacteria break down certain chemicals or compounds in the water or the soil, and how do they move that to the next part of the carbon cycle. We have no idea what milky seas mean in terms of that movement or partitioning of carbon in the ocean. It could mean absolutely nothing. It could mean this is actually really a good event in terms of capturing more carbon and sequestering it in the ocean, or it could be a massive carbon release.

HOST: What's the next step in your research?

HUDSON: The next step is trying to use this database to better predict, well actually just predict when milky seas will occur. Because if we want to sample one, we have to be able to know when and where they're going to happen. It's very variable, even in the regions where they happen a lot, if you'll even have one during a particular year. Even being able to say that next year is a good time to look for milky seas in this region would be a massive step forward in our understanding.

HOST: Well, here's to being able to predict it and getting to the right place at the right time. Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate it.

HUDSON: Yeah, thank you so as well for having me on. I love this.

OUTRO: That was CSU doctoral student, Justin Hudson, speaking about his research into the maritime phenomenon of milky seas. I'm your host, Stac y Nick, and you're listening to CSU's The Audit.